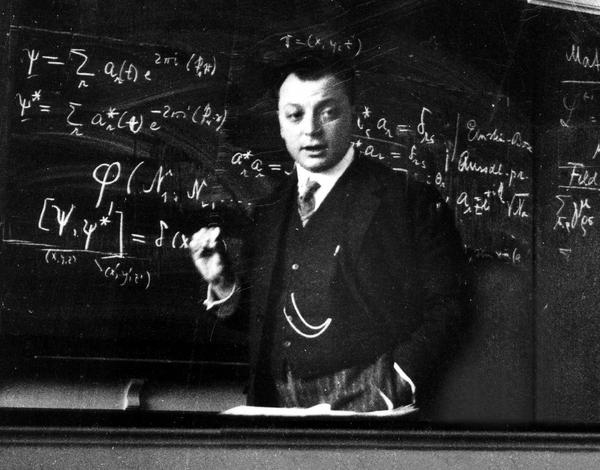

One hundred years ago this month, in December 1924, Wolfgang Pauli submitted a paper to Zeitschrift für Physik that provided the final piece of the puzzle that connected Bohr’s model of the atom to the structure of the periodic table. In the process, he introduced a new quantum number into physics that governs how matter as extreme as neutron stars, or as perfect as superfluid helium, organizes itself.

He was led to this crucial insight, not by his superior understanding of quantum physics, which he was grappling with as much as Bohr and Born and Sommerfeld were at that time, but through his superior understanding of relativistic physics that convinced him that the magnetism of atoms in magnetic fields could not be explained through the orbital motion of electrons alone.

Encyclopedia Article on Relativity

Bored with the topics he was being taught in high school in Vienna, Pauli was already reading Einstein on relativity and Emil Jordan on functional analysis before he arrived at the university in Munich to begin studying with Arnold Sommerfeld. Pauli was still merely a student when Felix Klein approached Sommerfeld to write an article on relativity theory for his Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences. Sommerfeld by that time was thoroughly impressed with Pauli’s command of the subject and suggested that he write the article.

Pauli’s encyclopedia article on relativity expanded to 250 pages and was published in Klein’s fifth volume in 1921 when Pauli was only 21 years old—just 5 years after Einstein had published his definitive work himself! Pauli’s article is still considered today one of the clearest explanations of both special and general relativity.

Pauli’s approach established the methodical use of metric space concepts that is still used today when teaching introductory courses on the topic. This contrasts with articles written only a few years earlier that seem archaic by comparison—even Einstein’s paper itself. As I recently read through his article, I was struck by how similar it is to what I teach from my textbook on modern dynamics to my class at Purdue University for junior physics majors.

Anomalous Zeeman Effect

In 1922, Pauli completed his thesis on the properties of water molecules and began studying a phenomenon known as the anomalous Zeeman effect. The Zeeman effect is the splitting of optical transitions in atoms under magnetic fields. The electron orbital motion couples with the magnetic field through a semi-classical interaction between the magnetic moment of the orbital and the applied magnetic field, producing a contribution to the energy of the electron that is observed when it absorbs or emits light.

The Bohr model of the atom had already concluded that the angular momentum of electron orbitals was quantized into integer units. Furthermore, the Stern-Gerlach experiment of 1922 had shown that the projection of these angular momentum states onto the direction of the magnetic field was also quantized. This was known at the time as “space quantization”. Therefore, in the Zeeman effect, the quantized angular momentum created quantized energy interactions with the magnetic field, producing the splittings in the optical transitions.

So far so good. But then comes the problem with the anomalous Zeeman effect.

In the Bohr model, all angular momenta have integer values. But in the anomalous Zeeman effect, the splittings could only be explained with half integers. For instance, if total angular momentum were equal to one-half, then in a magnetic field it would produce a “doublet” with +1/2 and -1/2 space quantization. An integer like L = 1 would produce a triplet with +1, 0, and -1 space quantization. Although doublets of the anomalous Zeeman effect were often observed, half-integers were unheard of (so far) in the quantum numbers of early quantum physics.

But half integers were not the only problem with “2”s in the atoms and elements. There was also the problem of the periodic table. It, too, seemed to be constructed out of “2”s, multiplying a sequence of the difference of squares.

The Difference of Squares

The difference of squares has a long history in physics stretching all the way back to Galileo Galilei who performed experiments around 1605 on the physics of falling bodies. He noted that the distance traveled in successive time intervals varied as the difference 12 – 02 = 1, then 22-12 = 3, then 32-22 = 5, then 42-32 = 7 and so on. In other words, the distances traveled in each successive time interval varied as the odd integers. Galileo, ever the astute student of physics, recognized that the distance traveled by an accelerating body in a time t varied as the square of time t2. Today, after Newton, we know that this is simply the dependence of distance for an accelerating body on the square of time s = (1/2)gt2.

By early 1924 there was another law of the difference of squares. But this time the physics was buried deep inside the new science of the elements, put on graphic display through the periodic table.

The periodic table is constructed on the difference of squares. First there is 2 for hydrogen and helium. Then another 2 for lithium and beryllium, followed by 6 for B, C, N, O, F and Ne to make a total of 8. After that there is another 8 plus 10 for the sequence of Sc, Ti, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn to make a total of 18. The sequence of 2-8-18 is 2•12 = 2, 2•22 = 8, 2•32 = 18 for the sequence 2n2.

Why the periodic table should be constructed out of the number 2 times the square of the principal quantum number n was a complete mystery. Sommerfeld went so far as to call the number sequence of the periodic table a “cabalistic” rule.

The Bohr Model for Many Electrons

It is easy to picture how confusing this all was to Bohr and Born and others at the time. From Bohr’s theory of the hydrogen atom, it was clear that there were different energy levels associated with the principal quantum number n, and that this was related directly to angular momentum through the motion of the electrons in the Bohr orbitals.

But as the periodic table is built up from H to He and then to Li and Be and B, adding in successive additional electrons, one of the simplest questions was why the electrons did not all reside on the lowest energy level? But even if that question could not be answered, there was the question of why after He the elements Li and Be behaved differently than B, N, O and F, leading to the noble gas Ne. From normal Zeeman spectroscopy as well as x-ray transitions, it was clear that the noble gases behaved as the core of succeeding elements, like He for Li and Be and Ne for Na and Mg.

To grapple with all of this, Bohr had devised a “building up” rule for how electrons were “filling” the different energy levels as each new electron of the next element was considered. The noble-gas core played a key role in this model, and the core was also assumed to be contributing to both the normal Zeeman effect as well as the anomalous Zeeman effect with its mysterious half-integer angular momenta.

But frankly, this core model was a mess, with ad hoc rules on how the additional electrons were filling the energy levels and how they were contributing to the total angular momentum.

This was the state of the problem when Pauli, with his exceptional understanding of special relativity, began to dig deep into the problem. Since the Zeeman splittings were caused by the orbital motion of the electrons, the strongly bound electrons in high-Z atoms would be moving at speeds near the speed of light. Pauli therefore calculated what the systematic effects would be on the Zeeman splittings as the Z of the atoms got larger and the relativistic effects got stronger.

He calculated this effect to high precision, and then waited for Landé to make the measurements. When Landé finally got back to him, it was to say that there was absolutely no relativistic corrections for Thallium (Z = 90). The splitting remained simply fixed by the Bohr magneton value with no relativistic effects.

Pauli had no choice but to reject the existing core model of angular momentum and to ascribe the Zeeman effects to the outer valence electron. But this was just the beginning.

Pauli’s Breakthrough

By November of 1924 Pauli had concluded, in a letter to Landé

“In a puzzling, non-mechanical way, the valence electron manages to run about in two states with the same k but with different angular momenta.”

And in December of 1924 he submitted his work on the relativistic effects (or lack thereof) to Zeitschrift für Physik,

“From this viewpoint the doublet structure of the alkali spectra as well as the failure of Larmor’s theorem arise through a specific, classically non-describable sort of Zweideutigkeit (two-foldness) of the quantum-theoretical properties of the valence electron. (Pauli, 1925a, pg. 385)

Around this time, he read a paper by Edmund Stoner in the Philosophical Magazine of London published in October of 1924. Stoner’s insight was a connection between the number of states observed in a magnetic field and the number of states filled in the successive positions of elements in the periodic table. Stoner’s insight led naturally to the 2-8-18 sequence for the table, although he was still thinking in terms of the quantum numbers of the core model of the atoms.

This is when Pauli put 2 plus 2 together: He realized that the states of the atom could be indexed by a set of 4 quantum numbers: n-the principal quantum number, k1-the angular momentum, m1-the space quantization number, and a new fourth quantum number m2 that he introduced but that had, as yet, no mechanistic explanation. With these four quantum numbers enumerated, he then made the major step:

It should be forbidden that more than one electron, having the same equivalent quantum numbers, can be in the same state. When an electron takes on a set of values for the four quantum numbers, then that state is occupied.

This is the Exclusion Principle: No two electrons can have the same set of quantum numbers. Or equivalently, no electron state can be occupied by two electrons.

Today, we know that Pauli’s Zweideutigkeit is electron spin, a concept first put forward in 1925 by the American physicist Ralph Kronig and later that year by George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit.

And Pauli’s Exclusion Principle is a consequence of the antisymmetry of electron wavefunctions first described by Paul Dirac in 1926 after the introduction of wavefunctions into quantum theory by Erwin Schrödinger earlier that year.

Timeline:

1845 – Faraday effect (rotation of light polarization in a magnetic field)

1896 – Zeeman effect (splitting of optical transition in a magnetic field)

1897 – Anomalous Zeeman effect (half-integer splittings)

1902 – Lorentz and Zeeman awarded Nobel prize (for electron theory)

1921 – Paschen-Back effect (strong-field Zeeman effect)

1922 – Stern-Gerlach (space quantization)

1924 – de Broglie matter waves

1924 – Bose statistics of photons

1924 – Stoner (conservation of number of states)

1924 – Pauli Exclusion Principle

References:

E. C. Stoner (Philosophical Magazine, 48 [1924], 719) Issue 286 October 1924

M. Jammer, The conceptual development of quantum mechanics (Los Angeles, Calif.: Tomash Publishers, Woodbury, N.Y. : American Institute of Physics, 1989).

M. Massimi, Pauli’s exclusion principle: The origin and validation of a scientific principle (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Pauli, W. Über den Einfluß der Geschwindigkeitsabhängigkeit der Elektronenmasse auf den Zeemaneffekt. Z. Physik 31, 373–385 (1925). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02980592

Pauli, W. (1925). “Über den Zusammenhang des Abschlusses der Elektronengruppen im Atom mit der Komplexstruktur der Spektren”. Zeitschrift für Physik. 31 (1): 765–783