Physicists of the nineteenth century were obsessed with mechanical models. They must have dreamed, in their sleep, of spinning flywheels connected by criss-crossing drive belts turning enmeshed gears. For them, Newton’s clockwork universe was more than a metaphor—they believed that mechanical description of a phenomenon could unlock further secrets and act as a tool of discovery.

It is no wonder they thought this way—the mid-eighteenth century was at the peak of the industrial revolution, dominated by the steam engine and the profusion of mechanical power and gears across broad swaths of society.

Steampunk

The Victorian obsession with steam and power is captured beautifully in the literary and animé genre known as Steampunk. The genre is alternative historical fiction that portrays steam technology progressing into grand and wild new forms as electrical and gasoline technology fail to develop. An early classic in the genre is Miyazaki’s 1986 anime´ film Castle in the Sky (1986) by Hayao Miyazaki about a world where all mechanical devices, including airships, are driven by steam. A later archetype of the genre is the 2004 animé film Steam Boy (2004) by Katsuhiro Otomo about the discovery of superwater that generates unlimited steam power. As international powers vie to possess it, mad scientists strive to exploit it for society, but they create a terrible weapon instead. One of the classics that helped launch the genre is the novel The Difference Engine (1990) by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling that envisioned an alternative history of computers developed by Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace.

Steampunk is an apt, if excessively exaggerated, caricature of the Victorian mindset and approach to science. Confidence in microscopic mechanical models among natural philosophers was encouraged by the success of molecular models of ideal gases as the foundation for macroscopic thermodynamics. Pictures of small perfect spheres colliding with each other in simple billiard-ball-like interactions could be used to build up to overarching concepts like heat and entropy and temperature. Kinetic theory was proposed in 1857 by the German physicist Rudolph Clausius and was quickly placed on a firm physical foundation using principles of Hamiltonian dynamics by the British physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

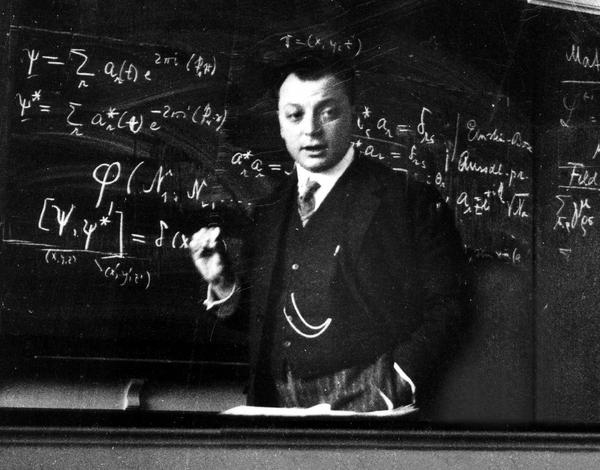

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (1831 – 1879) was one of three titans out of Cambridge who served as the intellectual leaders in mid-nineteenth-century Britain. The two others were George Stokes and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin). All three were Wranglers, the top finishers on the Tripos exam at Cambridge, the grueling eight-day examination across all fields of mathematics. The winner of the Tripos, known as first Wrangler, was announced with great fanfare in the local papers, and the lucky student was acclaimed like a sports hero is today. Stokes in 1841 was first Wrangler while Thomson (Lord Kelvin) in 1845 and Maxwell in 1854 were each second Wranglers. They were also each winners of the Smith’s Prize, the top examination at Cambridge for mathematical originality. When Maxwell sat for the Smith’s Prize in 1854 one of the exam problems was a proof written by Stokes on a suggestion by Thomson. Maxwell failed to achieve the proof, though he did win the Prize. The problem became known as Stokes’ Theorem, one of the fundamental theorems of vector calculus, and the proof was eventually provided by Hermann Hankel in 1861.

After graduation from Cambridge, Maxwell took the chair of natural philosophy at Marischal College in the city of Aberdeen in Scotland. He was only 25 years old when he began, fifteen years younger than any of the other professors. He split his time between the university and his family home at Glenlair in the south of Scotland, which he inherited from his father the same year he began his chair at Aberdeen. His research interests spanned from the perception of color to the rings of Saturn. He improved on Thomas Young’s three-color theory by correctly identifying red, green and blue as the primary receptors of the eye and invented a scheme for adding colors that is close to the HSV (hue-saturation-value) system used today in computer graphics. In his work on the rings of Saturn, he developed a statistical mechanical approach to explain how the large-scale structure emerged from the interactions among the small grains. He applied these same techniques several years later to the problem of ideal gases when he derived the speed distribution known today as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Maxwell’s career at Aberdeen held great promise until he was suddenly fired from his post in 1860 when Marischal College merged with nearby King’s College to form the University of Aberdeen. After the merger, the university had the abundance of two professors of Natural Philosophy while needing only one, and Maxwell was the junior. With his new wife, Maxwell retired to Glenlair and buried himself in writing the first drafts of a paper titled “On Physical Lines of Force” [2]. The paper explored the mathematical and mechanical aspects of the curious lines of magnetic force that Michael Faraday had first proposed in 1831 and which Thomson had developed mathematically around 1845 as the first field theory in physics.

As Maxwell explored the interrelationships among electric and magnetic phenomena, he derived a wave equation for the electric and magnetic fields and was astounded to find that the speed of electromagnetic waves was essentially the same as the speed of light. The importance of this coincidence did not escape him, and he concluded that light—that rarified, enigmatic and quintessential fifth element—must be electromagnetic in origin. Ever since Francois Arago and Agustin Fresnel had shown that light was a wave phenomenon, scientists had been searching for other physical signs of the medium that supported the waves—a medium known as the luminiferous aether (or ether). With Maxwell’s new finding, it meant that the luminiferous ether must be related to electric and magnetic fields. In the Steampunk tradition of his day, Maxwell began a search for a mechanical model. He did not need to look far, because his friend Thomson had already built a theory on a foundation provided by the Irish mathematician James MacCullagh (1809 – 1847)

The Luminiferous Ether

The late 1830’s was a busy time for the luminiferous ether. Agustin-Louis Cauchy published his extensive theory of the ether in 1836, and the self-taught George Green published his highly influential mathematical theory in 1838 which contained many new ideas, such as the emphasis on potentials and his derivation of what came to be called Green’s theorem.

In 1839 MacCullagh took an approach that established a core property of the ether that later inspired both Thomson and Maxwell in their development of electromagnetic field theory. What McCullagh realized was that the energy of the ether could be considered as if it had both kinetic energy and potential energy (ideas and nomenclature that would come several decades later). Most insightful was the fact that the potential energy of the field depended on pure rotation like a vortex. This rotationally elastic ether was a mathematical invention without any mechanical analog, but it successfully described reflection and refraction as well as polarization of light in crystalline optics.

In 1856 Thomson put Faraday’s famous magneto-optic rotation of light (the Faraday Effect discovered by Faraday in 1845) into mathematical form and began putting Faraday’s initially abstract ideas of the theory of fields into concrete equations. He drew from MacCullagh’s rotational ether as well as an idea from William Rankine about the molecular vortex model of atoms to develop a mechanical vortex model of the ether. Thomson explained how the magnetic field rotated the linear polarization of light through the action of a multiplicity of molecular vortices. Inspired by Thomson, Maxwell took up the idea of molecular vortices as well as Faraday’s magnetic induction in free space and transferred the vortices from being a property exclusively of matter to being a property of the luminiferous ether that supported the electric and magnetic fields.

Maxwellian Cogwheels

Maxwell’s model of the electromagnetic fields in the ether is the apex of Victorian mechanistic philosophy—too explicit to be a true model of reality—yet it was amazingly fruitful as a tool of discovery, helping Maxwell develop his theory of electrodynamics. The model consisted of an array of elastic vortex cells separated by layers of small particles that acted as “idle wheels” to transfer spin from one vortex to another . The magnetic field was represented by the rotation of the vortices, and the electric current was represented by the displacement of the idle wheels.

Two predictions by this outrightly mechanical model were to change the physics of electromagnetism forever: First, any change in strain in the electric field would cause the idle wheels to shift, creating a transient current that was called a “displacement current”. This displacement current was one of the last pieces in the electromagnetic puzzle that became Maxwell’s equations.

In this description, E is not the electric field, but is related to the dielectric permativity through the relation

Maxwell went further to prove his Proposition XIV on the contribution of the displacement current to conventional electric currents.

Second, Maxwell calculated that this elastic vortex ether propagated waves at a speed that was close to the known speed of light measured a decade previously by the French physicist Hippolyte Fizeau. He remarked, “we can scarcely avoid the inference that light consists of the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena.” [1] This was the first direct prediction that light, previously viewed as a physical process separate from electric and magnetic fields, was an electromagnetic phenomenon.

These two predictions—of the displacement current and the electromagnetic origin of light—have stood the test of time and are center pieces of Maxwells’s legacy. How strange that they arose from a mechanical model of vortices and idle wheels like so many cogs and gears in the machinery powering the Victorian age, yet such is the power of physical visualization.

[1] pg. 12, The Maxwellians, Bruce Hunt (Cornell University Press, 1991)

[2] Maxwell, J. C. (1861). “On physical lines of force”. Philosophical Magazine. 90: 11–23.